Hinduism

Hinduism is one of the oldest living religions and yet continues today as a healthy, colorful and exuberant tradition. It is classified as one of the main world religions with over 800 million followers. Strongly rooted in India and other parts of Asia, Hinduism is worldwide known through art, vegetarian cuisine, dress, and philosophy.

Hinduism is very prominently promoting that its teachings are relevant to all people at all times, accepting other religions as different paths towards the common goal of linking the soul with God. Consequently, scholars refer to Hinduism as ‘a family of religions’ or ‘a way of life’, more often called by Hindus ‘Sanatana Dharma’ (the eternal way of life).

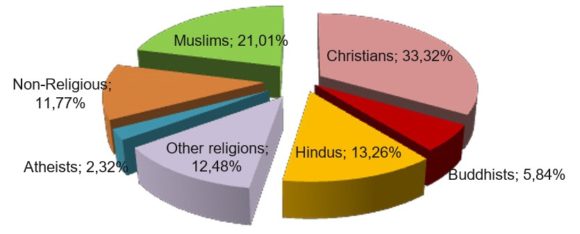

Hinduism is the largest religion in Asia and the world’s third-largest, in terms of numbers of followers. There are several different sources for Hindu population figures*. The consensus estimate of the current global population of Hindus is about 885 million. Hinduism has intimate links with India and Nepal, but its influence visibly extends throughout Asia to countries like Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Indonesia, Singapore, Bhutan, Indonesia- Bali etc. About 1 million followers are based in the UK. These tend to be descendants of Hindu immigrants. In recent times Hinduism has reached all corners of the world through immigration to Fiji, Mauritius, the Caribbean, America and South & East Africa.

* The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) places the percentage of Hindus in the world at around 13.26 out of the total world population of 6,677,563,921 (July 2008 est). Encyclopaedia Brittanica estimated the proportion of Hindus in the world at 13.33 percent in 2005. Meanwhile, the Foreign Policy magazine published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace gives the world Hindu population at 870 million as of May 2007, and growing at about 1.52 percent annually.

Hinduism is at least 4000 years old. Unlike most other religions, Hinduism has no single founder, no central authority or commonly agreed set of teachings.

The common denominator to all the traditions within Hinduism is the acceptance of the Vedas as revealed scriptures. Indeed according to the Supreme Court of India, Hinduism was legally defined in 1966 primarily as “Acceptance of the Vedas with reverence as the highest authority in religious and philosophical matters”. (Buddhism and Jainism though born in India are not included within the numerous varieties of Hindu doctrines and practices chiefly because both these traditions rejected the Vedas).

The word Hindu and Hinduism, though very practical and convenient for Scholars, outsiders, and even its followers, are nowhere to be found in any of the ancient Vedic scriptures written in the Sanskrit language, so perhaps a more appropriate way to refer to the different “Hindu” traditions could be “Vedic” traditions.

Hinduism has no single scripture but many. They include the Vedas and their corollaries sometimes called collectively “the Vedic scriptures” written in the Sanskrit language. There are two main divisions:

Hinduism has no single scripture but many. They include the Vedas and their corollaries sometimes called collectively “the Vedic scriptures” written in the Sanskrit language. There are two main divisions:

There are different opinions about the relative validity and importance of each. Some Hindus stress the foundational importance of Shruti, whereas others say that in making truths accessible, Smriti is more important today.

The shruti texts are considered to be more important but they are philosophical and difficult to understand. The Vedas are divided into 4:

The shruti texts are considered to be more important but they are philosophical and difficult to understand. The Vedas are divided into 4:

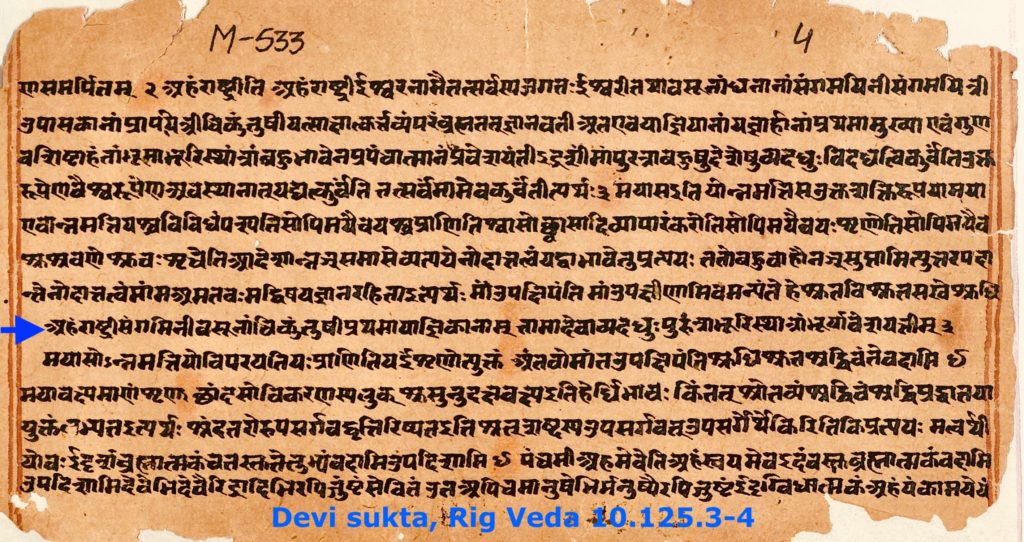

- The Rig Veda is the most important and the oldest and it is divided into 10 books with a total of 1028 hymns in praise of various deities. It also contains the famous Gayatri mantra and the prayer called the Purusha Sukta (the story of the Supreme Lord).

- The Yajur Veda is a priestly handbook for use in the performance of yajnas (sacrifices).

- The Sama Veda consists of chants and melodies to be sung during worship and performance of yajna.

- The Atharva Veda contains hymns, mantras and incantations, largely outside the scope of yajna.

Within each of these 4 books there are 4 types of composition or divisions:

- The Samhitas are literally “collections”, in this case of hymns and mantras.

- The Brahmanas are prose manuals of ritual and prayer for guiding priests. They tend to explain the Samhitas.

- The Aranyakas are literally “forest books” for hermits and saints. They are philosophical treatises.

- The Upanishads are the books of philosophy and are also called “Vedanta”, the end or conclusion of the Vedas.

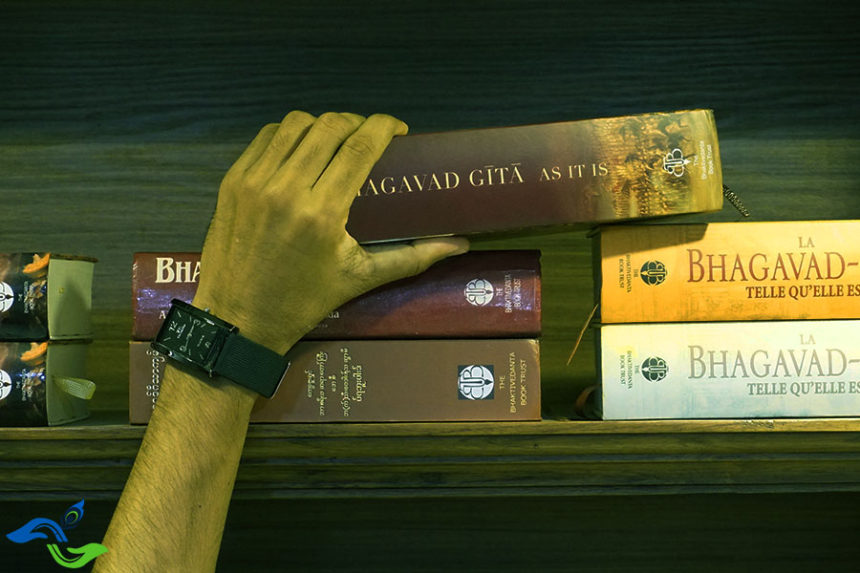

- The Itihasas include “histories” and great epics like the Mahabharata (110.000 verses) and the Ramayana, which are the most popular texts for Hindus. The Mahabharata includes the Bhagavad Gita (700 verses) which is a philosophical Smriti text and the most widely read book by Hindus. (It comes closest to what the Bible is for Christians and the Koran for Muslims).

- The Puranas include 18 Maha (great) Puranas and many Upa (subsidiary) Puranas. The Bhagavata Purana is the most popular.

- The Dharma Sastras are “law books” which include the famous Manu-smriti and the Vishnu- smriti.

- The Sutras are books of concise truths or aphorisms and include the Shrauta sutras, Shulba- sutras, Grihya-sutras, Vedanta-sutras, etc.

Rather than stressing the importance of everyone believing the same thing, Hinduism stresses the need for sincere spiritual practice. Despite the flexible approach towards belief, the following beliefs are shared:

Rather than stressing the importance of everyone believing the same thing, Hinduism stresses the need for sincere spiritual practice. Despite the flexible approach towards belief, the following beliefs are shared:

- Atman (soul)

- Samsara (reincarnation)

- Karma (action)

- Prakriti (matter)

- Gunas (qualities)

- Maya (illusion)

- Moksha (liberation)

- Bhagavan (God)

In order to understand the Hindu worldview, it is essential to grasp this first and foundational concept. Atman refers to the non-material self, which never changes. It is distinct from both the mind and the body. This real self is beyond the temporary designations we normally ascribe to ourselves, in terms of race, gender, species, and nationality. Consciousness, wherever it is found (in other words not only human beings), is considered a symptom of the soul, and without it the body has no awareness. In short, the atman or individual soul is spirit (Brahman), unchanging, eternal, and conscious while the body is material, temporary and unconscious. At death, the soul is carried within the subtle (astral) body into another body. The next body is determined by the state of mind at death, and by the soul’s desires.

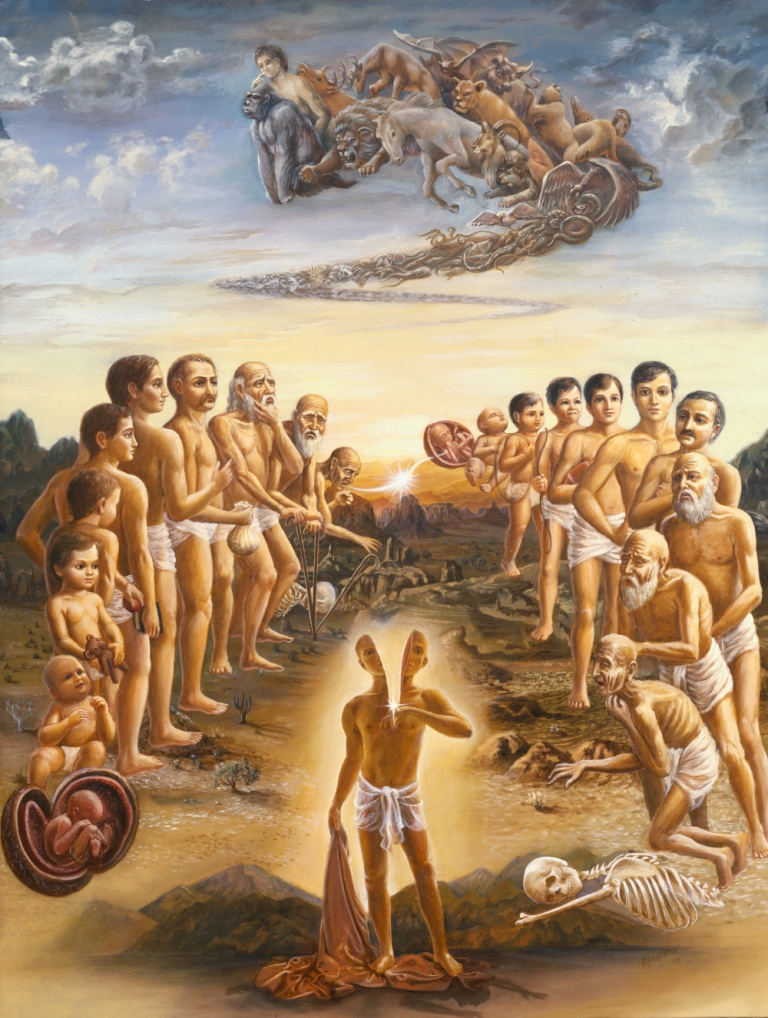

In order to understand the Hindu worldview, it is essential to grasp this first and foundational concept. Atman refers to the non-material self, which never changes. It is distinct from both the mind and the body. This real self is beyond the temporary designations we normally ascribe to ourselves, in terms of race, gender, species, and nationality. Consciousness, wherever it is found (in other words not only human beings), is considered a symptom of the soul, and without it the body has no awareness. In short, the atman or individual soul is spirit (Brahman), unchanging, eternal, and conscious while the body is material, temporary and unconscious. At death, the soul is carried within the subtle (astral) body into another body. The next body is determined by the state of mind at death, and by the soul’s desires.  Samsara or cycle of reincarnation refers to the process of passing from one body to another throughout all species of life. Hindus believe that consciousness is present in all life forms, even fish and plants. However, though the soul is present in all species, its potential is exhibited to different degrees. In aquatics and plants, it is most “covered”, practically asleep, whereas in humans it is most alert. This progression of consciousness is manifest throughout 6 broad “classes of life”, namely

Samsara or cycle of reincarnation refers to the process of passing from one body to another throughout all species of life. Hindus believe that consciousness is present in all life forms, even fish and plants. However, though the soul is present in all species, its potential is exhibited to different degrees. In aquatics and plants, it is most “covered”, practically asleep, whereas in humans it is most alert. This progression of consciousness is manifest throughout 6 broad “classes of life”, namely

- aquatics

- plants

- insects and reptiles

- birds

- animals and

- humans.

Most Hindus consider samsara essentially painful, a cycle of 4 recurring problems: birth, disease, old age, and death.

The universal law of karma (action and reaction) determines each soul’s unique destiny. The self-determination and accountability of the individual soul rest on its capacity for free choice. This is exercised only in the human form. Whilst in lower species, the atman takes no moral decisions but is instead bound by instinct. Therefore, although all species of life are subject to the reactions of past activities, such karma is generated only while in the human form. Human life alone is a life of responsibility. The Bhagavad Gita categorizes karma, listing 3 kinds of human actions:

The universal law of karma (action and reaction) determines each soul’s unique destiny. The self-determination and accountability of the individual soul rest on its capacity for free choice. This is exercised only in the human form. Whilst in lower species, the atman takes no moral decisions but is instead bound by instinct. Therefore, although all species of life are subject to the reactions of past activities, such karma is generated only while in the human form. Human life alone is a life of responsibility. The Bhagavad Gita categorizes karma, listing 3 kinds of human actions:

- Karma; those which elevate

- Vikarma: those which degrade and

- Akarma: those which create neither good nor bad reactions and thus lead to liberation.

Prakriti or matter is inert, temporary and unconscious. Everything made of matter undergoes 3 stages of existence:

Prakriti or matter is inert, temporary and unconscious. Everything made of matter undergoes 3 stages of existence:

- it is created

- it remains for some time and,

- it is inevitably destroyed.

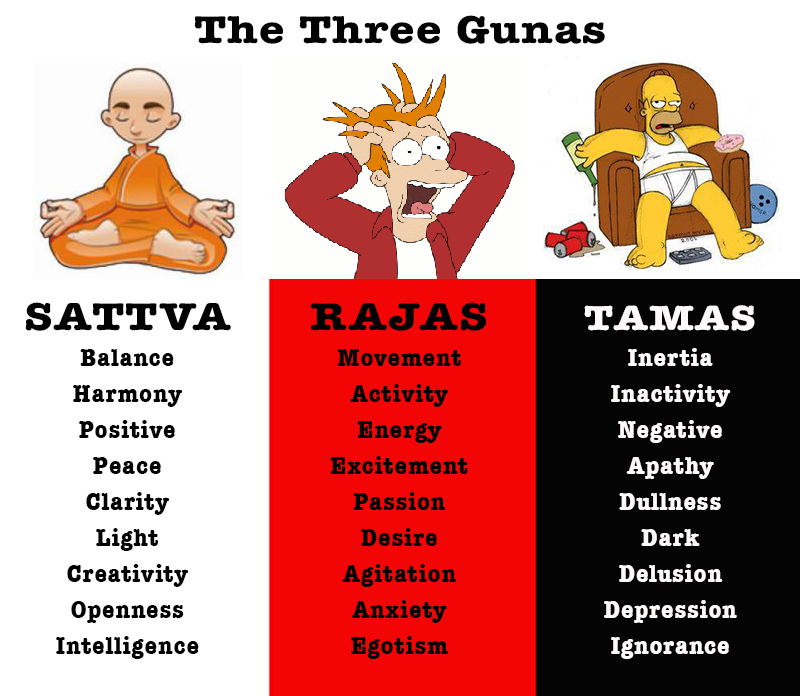

The matter is composed of 3 qualities (gunas) corresponding to creation, sustenance, and destruction. They are:

Sattva or goodness is pure, elevating, enlightening

Rajas or passion motivates us to create, acquire and enjoy

Tamas or ignorance is dirty, degrading, deluding, and destructive

All material phenomena can be analyzed in terms of the gunas. According to the soul’s preference for a particular mode, it takes on a corresponding body. Those influenced by goodness will be elevated to the heavenly planets at death, those largely influenced by passion stay in the human society and those influenced by ignorance enter into the lower species.

The matter is composed of 3 qualities (gunas) corresponding to creation, sustenance, and destruction. They are:

Sattva or goodness is pure, elevating, enlightening

Rajas or passion motivates us to create, acquire and enjoy

Tamas or ignorance is dirty, degrading, deluding, and destructive

All material phenomena can be analyzed in terms of the gunas. According to the soul’s preference for a particular mode, it takes on a corresponding body. Those influenced by goodness will be elevated to the heavenly planets at death, those largely influenced by passion stay in the human society and those influenced by ignorance enter into the lower species.  Maya or illusion means that which is not. Influenced by the 3 gunas the atman or soul mistakenly identifies with the body. He accepts such thoughts such as “I am white and I am a man”, or “This is my house, my country and my religion.” Thus the bewildered soul identifies with the temporary body and everything connected to it, such as race, gender, family, nation, bank balance and sectarian religion. Under this false identity, the atman aspires to control and enjoy matter. It is by cultivating the quality of goodness that the soul can make gradual progress towards transcendence and eventually fully escape the influence of any of the 3 gunas including goodness and obtain liberation.

Maya or illusion means that which is not. Influenced by the 3 gunas the atman or soul mistakenly identifies with the body. He accepts such thoughts such as “I am white and I am a man”, or “This is my house, my country and my religion.” Thus the bewildered soul identifies with the temporary body and everything connected to it, such as race, gender, family, nation, bank balance and sectarian religion. Under this false identity, the atman aspires to control and enjoy matter. It is by cultivating the quality of goodness that the soul can make gradual progress towards transcendence and eventually fully escape the influence of any of the 3 gunas including goodness and obtain liberation.  Moksha or liberation from Samsara, Maya and the influence of the 3 Gunas is considered by most Hindu traditions as the ultimate goal of life. The main difference of opinion centre on the precise nature of Moksha. Although practically all schools consider it a state of unity with God, the nature of such unity is contested. The Advaita or monistic traditions say that moksha entails annihilation of the soul’s false sense of individuality and realization of its complete non-difference from God. The Dvaita or dualistic traditions claim that God remains ever distinct from the individual soul or atman even after the soul has achieved liberation from its false identity; and union with God refers to a unity of purpose in which the individual soul surrenders, serves and loves the Supreme Brahman or God.

Moksha or liberation from Samsara, Maya and the influence of the 3 Gunas is considered by most Hindu traditions as the ultimate goal of life. The main difference of opinion centre on the precise nature of Moksha. Although practically all schools consider it a state of unity with God, the nature of such unity is contested. The Advaita or monistic traditions say that moksha entails annihilation of the soul’s false sense of individuality and realization of its complete non-difference from God. The Dvaita or dualistic traditions claim that God remains ever distinct from the individual soul or atman even after the soul has achieved liberation from its false identity; and union with God refers to a unity of purpose in which the individual soul surrenders, serves and loves the Supreme Brahman or God.

God is addressed by many names in Hinduism depending on the tradition or aspect of the Supreme Truth that one is trying to present. Many Hindus describe God as Sat-Cid-Ananda or full of eternity, knowledge and bliss. These correspond to three main features of the Supreme:

Brahman refers to the all-pervading aspect of God. Scripture states ‘everything is Brahman.” This sat/eternal aspect of God is realized by understanding one’s own eternal nature as atman.

Paramatman or Antaryami means “the controller within” and refers to God residing within the hearts of all beings. He is often referred to as the Supersoul and is initially perceived in various ways, through memory, instinct, intelligence, inspiration, and exceptional ability. He is the object of meditation for many mystic yogis. This feature of God represents his cit or knowledge aspect.

Bhagavan means “one endowed with unlimited opulence” and refers to God who lives beyond this material world. Bhagavan is the Supreme person and the individual soul can enter into a direct relationship with Him, thus experiencing ananda or spiritual pleasure.

Most traditions accommodate these three aspects of God, but will understand the relationship between them differently. They often stress one feature as more important than the others. They also differ as to the exact identity of God and their understanding of the many gods and goddesses.

God is addressed by many names in Hinduism depending on the tradition or aspect of the Supreme Truth that one is trying to present. Many Hindus describe God as Sat-Cid-Ananda or full of eternity, knowledge and bliss. These correspond to three main features of the Supreme:

Brahman refers to the all-pervading aspect of God. Scripture states ‘everything is Brahman.” This sat/eternal aspect of God is realized by understanding one’s own eternal nature as atman.

Paramatman or Antaryami means “the controller within” and refers to God residing within the hearts of all beings. He is often referred to as the Supersoul and is initially perceived in various ways, through memory, instinct, intelligence, inspiration, and exceptional ability. He is the object of meditation for many mystic yogis. This feature of God represents his cit or knowledge aspect.

Bhagavan means “one endowed with unlimited opulence” and refers to God who lives beyond this material world. Bhagavan is the Supreme person and the individual soul can enter into a direct relationship with Him, thus experiencing ananda or spiritual pleasure.

Most traditions accommodate these three aspects of God, but will understand the relationship between them differently. They often stress one feature as more important than the others. They also differ as to the exact identity of God and their understanding of the many gods and goddesses.

Het classificeren van de vele groepen binnen het Hindoeïsme is een uitdaging, meer dan bij andere religies. Door dit te doen, kunnen we onbewust het idee bevorderen dat het Hindoeïsme één enkele monolithische godsdienst is. Zoals eerder gezegd is het eerder een "familie van religies" waarbij elk familielid autonoom is maar wel onderscheidende familiekenmerken deelt. Het feit dat sommige Hindoeïstische tradities monotheïstisch zijn, andere monistisch en weer andere polytheïstisch, is een bewijs dat het Hindoeïsme sterk verschilt van andere wereldreligies. Als we proberen specifieke stromingen binnen het Hindoeïsme te onderscheiden, lopen we het gevaar te ver door te generaliseren, stereotypen te bevorderen en valse grenzen te trekken. Niettemin is het nuttig - zelfs noodzakelijk - om een enigszins voorlopig kader vast te stellen voor het categoriseren van de talrijke groepen en subgroepen.

De hoofdindeling van het Hindoeïsme is gebaseerd op de gerichtheid van de eredienst, die vier hoofdtradities oplevert:

1. Het Vaishnavisme is de grootste traditie binnen de familie van religies die Hindoeïsme wordt genoemd. Het is de oudste monotheïstische traditie in de wereld. Haar volgelingen, vaishnava's genaamd, aanbidden God onder de namen/vormen van Vishnu ("degene die alles doordringt"), Krishna ("de alom aantrekkelijke"), Rama ("de bron van alle plezier") of andere minder bekende namen/vormen of Avatars. Er zijn vier hoofdtakken of sampradaya’s van het vaishnavisme en vele subtakken. De theologen/stichters van deze 4 hoofdtakken of sampradaya’s zijn: Ramanuja, Madhva, Nimbarka en Vishnuswami. De belangrijkste Vedische geschriften die door de Vaishnava's worden bestudeerd en gevolgd zijn: Mahabharata, Ramayana, Bhagavad-Gita, Bhagavat Purana en Vedanta Sutras. De belangrijkste pelgrimsoorden voor de Vaishnava's zijn: Mathura/Vrindavana, Ayodhya, Puri, Dvaraka, Tirupati, Gurvayor, Shri Rangan, enz.

1. Het Vaishnavisme is de grootste traditie binnen de familie van religies die Hindoeïsme wordt genoemd. Het is de oudste monotheïstische traditie in de wereld. Haar volgelingen, vaishnava's genaamd, aanbidden God onder de namen/vormen van Vishnu ("degene die alles doordringt"), Krishna ("de alom aantrekkelijke"), Rama ("de bron van alle plezier") of andere minder bekende namen/vormen of Avatars. Er zijn vier hoofdtakken of sampradaya’s van het vaishnavisme en vele subtakken. De theologen/stichters van deze 4 hoofdtakken of sampradaya’s zijn: Ramanuja, Madhva, Nimbarka en Vishnuswami. De belangrijkste Vedische geschriften die door de Vaishnava's worden bestudeerd en gevolgd zijn: Mahabharata, Ramayana, Bhagavad-Gita, Bhagavat Purana en Vedanta Sutras. De belangrijkste pelgrimsoorden voor de Vaishnava's zijn: Mathura/Vrindavana, Ayodhya, Puri, Dvaraka, Tirupati, Gurvayor, Shri Rangan, enz.

2. Het Shaivisme is de op een na grootste traditie en heeft verschillende en belangrijke takken. Het wordt algemeen geassocieerd met ascese. Heer Shiva zelf wordt vaak afgebeeld als een yogi die in meditatie zit in de Himalaya’s. De belangrijkste Vedische geschriften die door de Shaivieten worden bestudeerd en gevolgd zijn: Svetashvatara Upanishad, Shiva Purana en de Agama’s. De belangrijkste pelgrimsoorden voor de Shaivieten zijn: Benares, Rameshvaram, Kedarnatha, Amarnatha, enz.

3. Shaktisme richt zich op de godin die algemeen "Devi" wordt genoemd. De Shakta traditie vereert specifiek Shiva's gemalin, in haar vele verschillende vormen zoals Parvati, Durga, Kali, enz. De belangrijkste Vedische geschriften die door de Shakta’s bestudeerd en gevolgd worden zijn: Devi Purana, Kalika Purana, Devi Bhagavata Purana en de Tantra’s. De belangrijkste pelgrimsoorden zijn: Bengalen, Calcutta (Kali Tempel), Kanyakumari, Madurai, Vaishno Devi, enz.

4.

2. Het Shaivisme is de op een na grootste traditie en heeft verschillende en belangrijke takken. Het wordt algemeen geassocieerd met ascese. Heer Shiva zelf wordt vaak afgebeeld als een yogi die in meditatie zit in de Himalaya’s. De belangrijkste Vedische geschriften die door de Shaivieten worden bestudeerd en gevolgd zijn: Svetashvatara Upanishad, Shiva Purana en de Agama’s. De belangrijkste pelgrimsoorden voor de Shaivieten zijn: Benares, Rameshvaram, Kedarnatha, Amarnatha, enz.

3. Shaktisme richt zich op de godin die algemeen "Devi" wordt genoemd. De Shakta traditie vereert specifiek Shiva's gemalin, in haar vele verschillende vormen zoals Parvati, Durga, Kali, enz. De belangrijkste Vedische geschriften die door de Shakta’s bestudeerd en gevolgd worden zijn: Devi Purana, Kalika Purana, Devi Bhagavata Purana en de Tantra’s. De belangrijkste pelgrimsoorden zijn: Bengalen, Calcutta (Kali Tempel), Kanyakumari, Madurai, Vaishno Devi, enz.

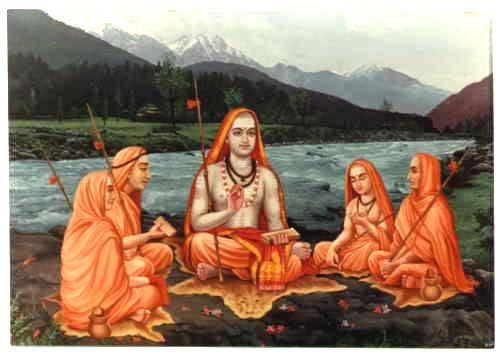

4.  Er is een vierde mainstream Hindoe traditie genaamd Smarta. De volgelingen van deze traditie worden de Smarta's genoemd en zijn traditioneel en zeer strikt wat betreft regels en voorschriften en benadrukken de universaliteit van het Hindoeïsme door zich te distantiëren van de exclusieve vereerders van Vishnu, Shiva of Devi. De belangrijkste theoloog van deze traditie is Shankaracharya of Adi Shankara, van wie wordt gezegd dat hij het systeem van de verering van 5 godheden heeft ingevoerd. Hij was de stichter van de Advaita School van Vedanta die aan de basis ligt van de wijdverspreide opvatting dat alle godheden gelijk zijn. De belangrijkste geschriften voor de Smarta’s zijn: Vedanta Sutra, Upanishads en Shariraka Bhasya. En de belangrijkste pelgrimsoorden zijn: Badrinatha, Puri, Kanchipuram, enz.

Er is een vierde mainstream Hindoe traditie genaamd Smarta. De volgelingen van deze traditie worden de Smarta's genoemd en zijn traditioneel en zeer strikt wat betreft regels en voorschriften en benadrukken de universaliteit van het Hindoeïsme door zich te distantiëren van de exclusieve vereerders van Vishnu, Shiva of Devi. De belangrijkste theoloog van deze traditie is Shankaracharya of Adi Shankara, van wie wordt gezegd dat hij het systeem van de verering van 5 godheden heeft ingevoerd. Hij was de stichter van de Advaita School van Vedanta die aan de basis ligt van de wijdverspreide opvatting dat alle godheden gelijk zijn. De belangrijkste geschriften voor de Smarta’s zijn: Vedanta Sutra, Upanishads en Shariraka Bhasya. En de belangrijkste pelgrimsoorden zijn: Badrinatha, Puri, Kanchipuram, enz.

Een ander criterium voor het classificeren van de volgelingen van het Hindoeïsme zijn de spirituele processen of paden die zij kiezen. Hoewel er binnen het Hindoeïsme vele verschillende praktijken bestaan, vallen de meeste onder 4 hoofdpaden of marga’s. Aangezien deze paden gericht zijn op vereniging (met God) worden zij ook wel "yoga’s" genoemd. Zij zijn:

- Karma Marg/Yoga of het pad van (juiste) actie

- Jnana Marg/Yoga of het pad der kennis

- Raja (Astanga) Marg/Yoga of het pad van meditatie

- Bhakti Marg/Yoga of het pad van devotie

De vier belangrijkste denominaties geven vaak de voorkeur aan een of meer van deze paden, bijvoorbeeld de Vaishnava's geven de voorkeur aan het pad van devotie, de Shaivieten aan het pad van kennis en meditatie, de Shakta's aan het pad van juiste actie en de Smarta's aan het pad van kennis.

Five practices are considered essential to the spiritual well-being and they focus on developing awareness of a person’s own spiritual nature and their relationship with the Supreme (God):

Five practices are considered essential to the spiritual well-being and they focus on developing awareness of a person’s own spiritual nature and their relationship with the Supreme (God):

- Dharma: living a virtuous life by performing our duties according to who we are.

- Worship: worship is often a personal matter which can be performed alone, in prayer, and in meditation. Worship is done often at home and in the temple on any day of the week.

- Festivals: the main purpose is to deepen the relationship with the Supreme, get inspiration and create a spiritual atmosphere.

- Pilgrimage: visiting a holy place connected to a certain deity is done while accepting voluntary austerity such as celibacy. Popular is a pilgrimage to the river Ganges considered to relieve one from sins.

- Rites of passage: the concept of reincarnation makes life an ongoing journey with four stages in life (student life, householder life, retired life and renounced life). To pass through each period in life, rituals or samskaras help to purify the soul so that it can be free from selfish thoughts or actions.

Although Hinduism places great value on ultimate detachment from worldly pleasure, it simultaneously stresses the importance of family stability. Great respect was traditionally given to family elders, who would offer guidance to younger members. Vedic teachings state that a good government looks after five sections of society: women, children, animals, holy people and the elderly. The goal is to protect the weak and not to exploit them.

Hospitality and humility, the two most important values of Hinduism are based on the core belief that everyone is part of the divine.

Hinduism instructs the individual to practice truth, cleanliness, compassion, and renunciation. These instructions stimulate a lifestyle of non-violence, a balanced diet including vegetarianism, and a healthy lifestyle. More on the level of the society, the scriptures mention the benefits of the natural life of planting trees, protecting wildlife, and avoiding pollution. It warns against greed and recommends sustainability and long-term vision as important moral principles.

The famous holy verse in Hinduism ‘Vasudaiva kutumbakam’’ meaning ‘the world is one family’ includes not only humans, but all other forms of life. In all living beings, the soul is present and despite the different ways we think of God, he (and she) is the same for all of us. This is the core message of Hinduism, the Sanatana Dharma.

Although Hinduism places great value on ultimate detachment from worldly pleasure, it simultaneously stresses the importance of family stability. Great respect was traditionally given to family elders, who would offer guidance to younger members. Vedic teachings state that a good government looks after five sections of society: women, children, animals, holy people and the elderly. The goal is to protect the weak and not to exploit them.

Hospitality and humility, the two most important values of Hinduism are based on the core belief that everyone is part of the divine.

Hinduism instructs the individual to practice truth, cleanliness, compassion, and renunciation. These instructions stimulate a lifestyle of non-violence, a balanced diet including vegetarianism, and a healthy lifestyle. More on the level of the society, the scriptures mention the benefits of the natural life of planting trees, protecting wildlife, and avoiding pollution. It warns against greed and recommends sustainability and long-term vision as important moral principles.

The famous holy verse in Hinduism ‘Vasudaiva kutumbakam’’ meaning ‘the world is one family’ includes not only humans, but all other forms of life. In all living beings, the soul is present and despite the different ways we think of God, he (and she) is the same for all of us. This is the core message of Hinduism, the Sanatana Dharma.